LINCOLN’S GETTYSBURG ADDRESS & BEING TRUE TO YOURSELF

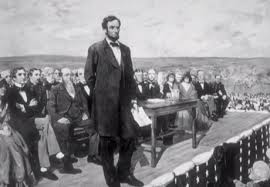

As a school student I, along with everyone else in my generation, was introduced to Lincoln's famous speech during the civil war now known as the Gettysburg Address. I've often thought of this address as an illustration of Lincoln's following his own analysis of who he was and what he thought best. Here he was, the president of the United States, and his invitation to speak was only an after thought to the event. His invitation was a last minute one and then asked only to make a few appropriate remarks because the main speaker was a nationally known orator who planned to speak for two hours. Yet Lincoln did not refuse the invitation nor decide  to compete with the main speaker's oratorical skills.

to compete with the main speaker's oratorical skills.

Instead he used it as an occasion to speak out for the principle of human equality, asserting that the Declaration of Independence and not the constitution was the true expression of the founding fathers who believed in equal rights for all people.

Lincoln was true to himself which is a wise thing to do. We read in 1 Corinthians 15 Paul saying: "By the grace of God I am what I am…" And the once popular newspaper comic character, Popeye the Sailor Man, frequently pointed out: "I yam what I yam and that's l what I yam." Then there was the late Sammy Davis Jr. who made popular the song "I've Gotta Be Me" with the lyrics:

"Whether I'm right or whether I'm wrong

Whether I find a place in this world or never belong

I gotta be me, I've gotta be me

What else can I be but what I am."

Margery Williams, in her classic children's book The Velveteen Rabbit, has the Skin Horse explaining what "being real" means:

“Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby. But these things don't matter at all, because once you are Real you can't be ugly, except to people who don't understand.”

I seen Lincoln, on this occasion, having the courage to being real and being true to himself by the address he gave that day. What is notable is that his short, two minute address given in November of 1863 has been treasured for 150 years so there is something unique about it. Let's remember Lincoln's Gettysburg address contained only 271 words and 202 of the words were just one syllable, so it wasn't complicated, nor lengthy nor equal to the eloquence of the main speaker. What is truly significant is that no one remembers any part of Everett's two hour speech, but Lincoln's two minute talk has endured. What is also significant is the simplicity of the talk. His words were simple, understandable and brief with profound meaning. A lesson for all who have something important to say

So, what was the occasion for these speeches and the ceremony? It involved a battle during the civil war between the North and the South. During the late stages of the war Gen. Robert E. Lee concentrated his army around the small town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania while waiting for the approach of Union Gen. George G. Meade’s forces. On July 1, 1863 they engaged. The next day Confederates pushed back and exploited a weak Federal line at Barlow’s Knoll. The following day saw Lee strike the Union flanks, leading to heavy battle at different areas including East Cemetery Hill.

On the final day, July 3rd, fighting raged with the Union regaining its lost ground. After being cut down by a massive artillery bombardment in the afternoon, Lee attacked the Union center on Cemetery Ridge and was repulsed in what is now known as Pickett’s Charge. Lee's second invasion of the North had failed, and had resulted in heavy casualties; an estimated 51,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, captured, or listed as missing after Gettysburg.

Because, like all the battles of the civil war, the dead were quickly buried in unmarked graves, it was decided to hold a memorial for the dead who died during this critical battle. The chosen speaker for the event was Edward Everett, but he declined the original date selected because he said he needed more time to prepare. Everett, the former president of Harvard College, former U.S. senator and former secretary of state, was at the time one of the country’s leading orators.

On November 2, just weeks before the event, almost as an afterthought by the planners, an invitation was extended to President Lincoln, asking him to "make a few appropriate remarks. Despite popular stories, historians agree that Lincoln did not whip up his "remarks" on the back of an envelope enroute from Washington. He wrote at least half or more of it on White House stationery before his trip, and in his room the night before.

On the morning of November 19, Everett delivered his two-hour oration, without notes, about the Battle of Gettysburg and its significance. Then the orchestra played a hymn composed for the occasion. Lincoln then rose to the podium and addressed the crowd of some 15,000 people. He spoke for less than two minutes.

Later the newspapers roundly criticized his talk for lacking the eloquence expected by the crowd. One reporter called it "an insult to the memory of the dead." Another wrote of it, "We Pass over the silly remarks of the president." A third reporter called Lincoln's words "flat and dish watery." And even Lincoln himself said in his speech "The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here." They were all wrong. Today the Gettysburg address ranks among the greatest literary treasures of history. Here's what Lincoln said to the crowd that day:

"Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth."

Abraham Lincoln November 19, 1863